On 8 September 2020, the annual OECD Education at a Glance report was published. Inevitably, this year’s report focused on the impact of coronavirus on education provision and students across OECD countries. It also had a heavy focus on vocational training and its importance.

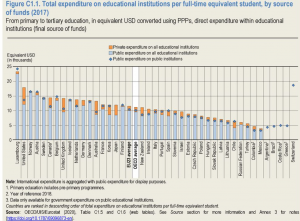

Total expenditure on educational institutions:

On average, OECD countries spend USD 11 000 per student on primary to tertiary educational institutions, which represents approximately USD 10 000 per student at primary, secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary level, and USD 16 300 at tertiary level.

Total expenditure on educational institutions for OECD countries, compared to the OECD average, can be seen in the table below.

(OECD Education at a Glance, 2020)

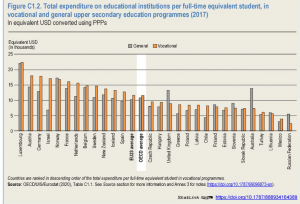

Total expenditure on educational institutions per full-time equivalent student, in vocational and general upper secondary education programmes:

(OECD Education at a Glance, 2020)

The key take-home points related to coronavirus and education are as follows:

- PUBLIC FINANCING OF EDUCATION IN OECD COUNTRIES:

- According to the OECD’s latest Economic Outlook, even if a second wave is avoided, global economic activity is expected to fall by 6% in 2020, with average unemployment in OECD countries climbing to 9.2% from 5.4% in 2019 (OECD, 2020).

- Government funding ‘often fluctuates in response to external shocks, as Government’s re-prioritise investments.’ The virus may therefore impact the availability of public funding for education in OECD countries, as tax income declines and money is funneled into supporting other sectors.

- However, it may take a ‘few years’ to notice this impact, particularly given that many OECD countries introduced short term financial measures to support the sector.

- INTERNATIONAL STUDENT MOBILITY:

- ‘The crisis has affected the continuity of learning and the delivery of course material, the safety and legal status of international students in their host countries, and students’ perception of the value of their degrees.’

- Not all OECD countries offered leniency with visa regulations, such as the United Kingdom or Canada.

- Higher education institutions have had to transition to online learning, however ‘many universities have struggled and lacked the experience and time needed to conceive new ways to deliver instruction and assignments.’

- Examinations were affected, which impacted students’ learning trajectories and progression.

- Students are also losing out on international mobility such as international exposure, access to foreign job markets and networking.

- A survey of EU students studying in the UK found that the main reasons for choosing to study abroad were to broaden their horizons or experience other cultures, improve their competence in English and improve their labour market prospects (West, 2000).

- Impacting funding models: the funding models of some higher education institutions will be impacted, where international students pay higher tuition fees than domestic ones.

- ‘Countries such as Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States, that rely heavily on international students paying differentiated fees will suffer the highest losses.’

- There will also be an impact on the value proposition of universities: ‘Students are unlikely to commit large amounts of time and money to consume online content’… ‘to remain relevant, universities will need to reinvent learning environments so that digitalization expands and complements, but does not replace, student-teacher and student-student relationships.’

- The enrolment of international students for the next academic year severely compromised, this will cut into universities’ core education services and the financial support they provide, as well as R&D activities.

- OECD countries relied on international student mobility to facilitate immigration of foreign talent: a decline in international student mobility in OECD countries such as Australia, New Zealand and the UK, risks affecting productivity in advanced sectors related to innovation and research in the years to come.

- Need to find a solution that ‘addresses the needs of an international student population that may be less willing to cross borders for the sole purpose of study.’

- THE LOSS OF INTRUCTIONAL TIME DEVLIVERED IN A SCHOOL SETTING

- It is difficult to estimate accurately the number of affected in countries, as some countries’ individual schools or local authorities have autonomy over the organisation of the school year and the reopening of schools.

- However, by the end of June 2020, some degree of school closure was effective for at least 7 weeks in 2 countries (4%), 8-12 weeks in 6 countries (13%), 12-16 weeks in 24 countries (52%), 16-18 weeks in 13 countries (28%), and more than 18 weeks in China (UNESCO, 2020).

- MEASURES TO CONTINUE STUDENTS’ LEARNING DURING SCHOOL CLOSURE:

- According to the OECD report, online platforms were used in nearly all OECD and partner countries, such as educational content for exploring, real-time lessons on virtual meeting platforms, online support services for parents and students, and self-paced formalised

- TV programmes, for example were widely used in Greece, Korea and Portugal. However, they were limited to covering only a few subjects due to the short amount of time devoted to TV programmes. Two channels in Spain covered 1 of 5 subjects per day during a one hour slot (Ministry of Education and Vocational Training, 2020, Schleicher and Reimers 2020).

- TEACHERS PREPAREDNESS TO SUPPORT DIGITAL LEARNING:

- ’The covid-19 crisis struck at a point when most of the education systems covered by the OECD’s 2019 round of the Programme for International Student Assessment were not ready for the world of digital learning opportunities.’

- ‘Technology is only as good as its use’: Younger teachers use technology more frequently in the classroom, but only 60% of teachers received professional development in ICT in the year preceding the survey, while 18% reported a high need for development in the area.

- ‘These figures highlight that teachers need to renew their skills regularly in order to be able to innovate their practices and adapt to the rapid transformations inherent in the 21 century. This is even more important in the current context.’

- Teachers also need ICT skills for their own professional development: on average across OECD countries, 36% of lower secondary teachers reported participating in online courses or seminars, less than half the share participating in courses or seminars in person.

- VOCATIONAL EDUCATION DURING THE COVID-19 LOCKDOWN:

- This year’s OECD report places the spotlight on the importance of vocational training.

- 42% of upper secondary students are enrolled in vocational education and training (VET), and 1 in 3 are enrolled in combined school and work-based programmes. 25-90% of the VET curriculum in these programmes is organised in the workplace (as an average across OECD countries).

- ‘With an economic crisis looming, it is still an open question whether companies will be able to take on apprentices as they struggle to recover from the economic setback.’

- The pandemic has created considerable uncertainty over what will happen next, and the ‘VET programmes that rely most heavily on practical changes will struggle the most to adjust to remote learning.’

- The report suggests that in many countries, there is an understanding that apprenticeship streams should not be the first victims of the current situation., and many have already taken steps. These steps include:

- increasing the use of online and virtual platforms more appropriate to VET to ensure continuity of learning.

- financing training breaks or extensions to avoid breaks in learning resulting in fees, repayments or other penalties for both learners and providers.

- providing wage support for apprentice retention to allow apprentices to maintain contact with employers and if possible continue working through remote working or virtual meetings.

- leveraging links between work-based and school-based VET to provide alternative school-based VET in cases where upper secondary VET students are unable to secure an apprenticeship, including work-based components.

- offering flexible skills assessment and awarding of qualifications as, in many sectors, particularly healthcare, a direct route to qualification may need to be established quickly in response to the COVID-19 crisis.

- informing, engaging and communicating with learners, providers and social partners about new guidance on the delivery of assessment, or to ensure apprentices are informed of changes to regulations and practices.

- investing in VET to mitigate future skills shortages and minimise the shock of the crisis.

Other key points from the OECD report, include:

- The employment advantage of an upper secondary vocational qualification over a general one tends to weaken over the course of one’s life

- More than 2/3rds of VET students are enrolled at upper secondary level. However, the employment advantage of a vocational qualification weakens over the life-course.

- On average across OECD countries, the employment rate of 25-34 year old adults with an upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary vocational qualification (82%) is similar to that among 45-54 year old’s (83%), whereas employment increases from 73% to 80% among those with a general qualification.

- In contrast, the employment advantage for tertiary-educated adults widens among older age groups.

- Earnings are also lower. While adults with an upper secondary vocational qualification have similar earnings to those with a general one, they earn 34% less than tertiary-educated adults on average across OECD countries.

- Combined school and work-based learning is relatively uncommon despite the benefits

- The countries with strong integrated school and work-based learning placements are those with the highest employment rates for adults with vocational qualifications, even surpassing those for tertiary-educated adults in some cases.

- Enabling VET students to pursue tertiary studies can improve their learning and employment outcomes

- On average across OECD countries, almost 7 out of 10 upper secondary vocational students are enrolled in programmes that provide direct access to tertiary education after completion. Vocational students are more likely to complete their qualification if their programme provides direct access to tertiary education than if it does not.

- The most common direct route from upper secondary vocational programmes to tertiary education is through short-cycle tertiary programmes, which are predominantly vocational in most OECD countries, but also through bachelor’s programmes or equivalent.

- On average across OECD countries, 17% of first-time tertiary entrants enter short-cycle tertiary programmes. The employment rate of adults with a short-cycle tertiary degree is four percentage points higher than those with an upper secondary vocational attainment and they earn 16% more on average across OECD countries.

- Total spending on educational institutions has increased at a lower rate than GDP

- After increasing between 2005 and 2012, total expenditure on primary to tertiary institutions as a share of GDP has fallen to 4.9% in 2017 on average, below its 2005 value of 5.1%. This is due to educational expenditure rising more slowly than GDP over this period, growing by 17% while GDP grew by 27%.

- The number of international and foreign tertiary students has grown on average by 4.8% per year between 1998 and 2018

The full report can be read here.

The insights report into coronavirus and education can be read here.